September 20, 2015

These were the top selling singles in the UK in 1975:

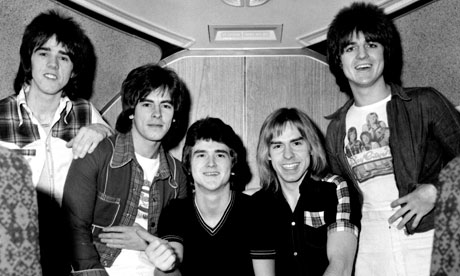

1 “Bye Bye Baby” – Bay City Rollers

2 “Sailing” – Rod Stewart

3 “Can’t Give You Anything (But My Love)” – The Stylistics

4 “Whispering Grass” – Windsor Davies and Don Estelle

5 “Stand by Your Man” – Tammy Wynette

6 “Give a Little Love” – Bay City Rollers

7 “Hold Me Close” – David Essex

8 “The Last Farewell” – Roger Whittaker

9 “I Only Have Eyes for You” – Art Garfunkel

10 “Tears On My Pillow” – Johnny Nash

11 “I’m Not in Love” – 10cc

12 “Barbados” – Typically Tropical

13 “If” – Telly Savalas

14 “There Goes My First Love” – The Drifters

15 “Three Steps to Heaven” – Showaddywaddy

This was pop music with its head in the sand.

As the last US helicopter left Saigon, in the UK, IRA bombs went off across the country, Margaret Thatcher comprehensively won the Conservative leadership race, National Front demos grew dramatically in number, inflation reached a record high and unemployment exceeded 1.25 million. And pop music had nothing to say, and nothing much to offer. Kids were bored, restless and angry.

And then 1976 rolled around.

The Clash could only have come from one place and time, specifically the patch of West London between Holland Park Avenue and the Westway spur, in these mid-to-late nineteen-seventies.

From his grandmother’s high-rise council flat on the Harrow Road, Mick Jones played guitar in a noisy mess of a band called London SS (zero gigs, one demo in 1975). Frustrated by failed auditions, and electrified by a Sex Pistols gig in February, Jones and manager Bernard Rhodes decided to form a new band, eventually recruiting Keith Levene on guitar, Paul Simonen on bass and Terry Chimes on drums (the rhythm section had both failed auditions for London SS).

They needed a voice, and were made aware of an older boy with a croaky voice who had seen the future at a Pistols’ gig.

John ‘Woody’ Mellor was fronting the 101’ers from 1974 onwards, a middle player adrift in the pub rock scene, led by the likes of Dr. Feelgood and Eddie and the Hot Rods. Already displaying a chameleon like tendency, he changed his name to better reflect his time busking with a ukulele on the Underground. Late in May, Rhodes and Levene met this Joe Strummer, and within days he was convinced to jump ship to front the band “who would rival the Pistols”. Their name came from a word which had been in most headlines that early summer, as riots, trade union clashes and political fall-outs dominated the press: the Clash.

In a frontman they found one of the most iconic of all time. All at once big-hearted, modest, funny, romantic and sincere, Joe Strummer bought harmony to the Clash.

Punk had exploded out of the cultural impasse, all at once and very quickly. Its role as the cartoon villains of 1976 was almost instantaneous; accelerating what was at once a wholly unique, ironic and complicated phenomenon into a cliché in itself – the ungrateful, sweary, snotty kids, walking Mohicans and safety pins. But for millions at the turn of 1976, poverty and anger weren’t fashion statements.

Punk rock burst into the face of Middle England as the embodiment of youthful frustration. And the Sex Pistols were the bourgeoisie nightmare made flesh. They were an immediate political force because they were seemingly so apolitical. They were the flag bearers for all their generation’s bottled-up anger and energy – and they vented it into extreme, base negativity. Their snarl punched a hole through the stalemate settling over England.

It was at once thrilling and inherently ambiguous: did these people care about anything?

The Clash cared. In contrast to the Pistols’ nihilism, The Clash were strikingly, endearingly earnest. They were romantic and very human: the last gang under the Westway.

1976 was Joe Strummer’s Year Zero, in which punk would bring the faded and jaded rock and pop of the 70s to its knees. But out of the ashes something thrilling could be built. And they set about reconstructing what the Pistols were tearing down. Whilst Johnny Rotten sneered that there was “no future”, The Clash were fighting for a better one.

In the long, hot summer of 1976, the pernicious rise of the far-right hung in the air. Enoch Powell sat in the back benches of Parliament, and in front of him Margaret Thatcher went on the offensive, attacking the government for its immigration policies. The National Front registered nearly a fifth of the votes in the Leicester by-election. Openly racist behaviour was prevalent on the streets and in the crowds, as far-right groups began to plug themselves into the loyalties of the disaffected youth. The whole country, its heroes, rebels, politicians – and punks – seemed to be flirting with fascism.

The Clash wore their beliefs on their sleeves, and fought back. What they wanted to create, within the very heart of the movement, was a social conscience; something which cared about the world around it. They bought a heart to punk – and a fundamental decency.

They weren’t wrong to look for humanism. Punk, after all, was a community. A messy, sometimes violent community, but a shelter for outsiders: a majority of minorities. If you feel outcast because of your age, gender, sexuality, class, race: loud music can save your life. Punk music came along, so sudden and sure-footed in its role in the national consciousness, that people could find themselves in its sarcasm and aggression.

And punk was fundamentally creative. The community began to be associated with a DIY ethos, as a throng of fans began creating and spreading zines like SNIFFIN’ GLUE, and a network sprang up. From their first gig in July ’76, the Clash name was front and centre. They took up the mantle with a vigour and ambition which seemed fixated on saving the scene and the country from itself.

The Clash were never shy about the influence and inspiration they took from black musical heritage, they wore it as a badge of honour – an outward display of camaraderie.

Based in multicultural West London, they soaked up their surroundings and infused it into angry, smart, energised pop. They sang about riots and supermarkets; motorways, dead-end jobs and letter bombs. Their sound had fury, intelligence and compassion, with rhythm inhaled from the reggae and dub vibrating from Portobello Road, and an attitude born in the shadows of London’s brutalist, post-war landscape – this was their city, and they sound-tracked it with a relish and romance that the Pistols never had.

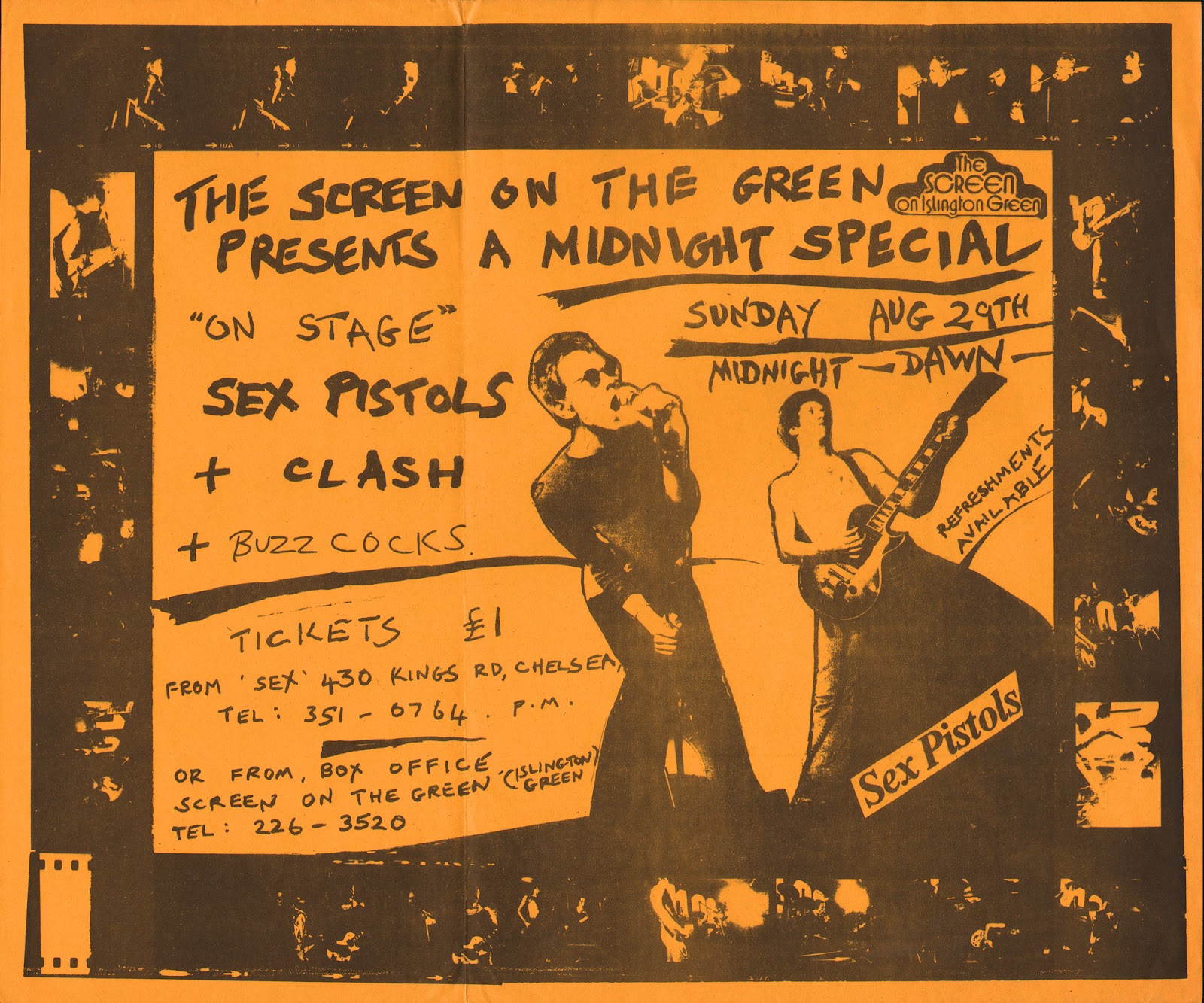

The long weekend of late August 1976 was pivotal for the Clash. Britain had sweltered through sustained droughts since May, and the band has spent the summer indoors, relentlessly rehearsing. It was as if they knew how important it all was, and how fast their ascent would be. On the 29th, the Clash played their first gig since their debut five weeks previously, at the Screen on the Green gig in Islington, alongside Buzzcocks and the Pistols.

The scene now had a core, and the momentum of a runaway train, and the Clash were at its heart after only two gigs.

The next day was the Bank Holiday Monday, a celebratory respite after a turbulent summer. On a bright, baking day Strummer, Simonen and Rhodes headed back West to attend the Notting Hill Carnival. The parade was in its tenth year, but recently dogged by increasing distrust between the police and the young, mostly black, attendees. The police had responded by increasing their presence by nearly 1,500: chaos ensued. In the early evening, in the shade of the Westway, a major riot broke out. Thrown back against wire fencing, Strummer saw police brutality against black youth, and a resistant spirit. It wasn’t his fight.

In response, the Clash penned ‘White Riot’, a blistering wail of an anthem. This was Joe Strummer’s primal scream for white working class youth to both show fierce racial solidarity, and to take up arms. It would be their debut single.

Invigorated, they emerged for the Punk Special at the 100 Club on the 20th of September. Headlined by the Pistols, the bill also included Buzzcocks, the Subway Sect, the Damned and Siouxsie and the Banshees (in their first gig). It marked the best and worse of the scene: electric, shambolic, and marred by mindless violence when a glass thrown by Sid Vicious blinded a girl in the eye.

1977. In one of the year’s first and most divisive moves, The Clash signed for CBS on 25th January. This came a month after the Sex Pistols had caused national outcry on the light entertainment Today show, when Steve Jones called a clearly drunk and antagonistic host Bill Grundy a “fucking rotter”. “THE FILTH AND THE FURY” read the tabloids the next day. It was the sort of shock the band craved, but for some it was turning punk into a clownish farce, before the year was even through.

The Clash deal was a statement of intent, to force the public to take the movement seriously.

They were becoming cutthroat, with Keith Levene and Terry Chimes replaced (for supposed laziness and a hint of Conservatism, respectively). Chimes would later be credited as “Tory Crimes” on their debut album, which arrived in April.

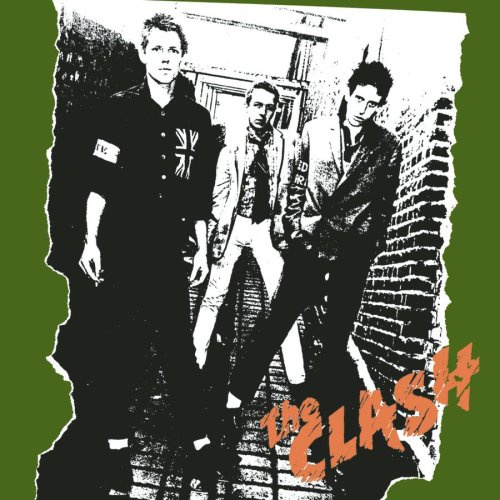

The Clash was released on the 8th. It remains a raw, howling triumph. Here, at last, was a full length statement on the state of the crumbling nation. Following an IMF bailout at the turn of the year, inflation remained in double digits. In the spring there were widespread British Leyland strikes, and PM James Callaghan barely survived a vote of no confidence. A fourth woman was killed in the North, at the hands of an elusive Yorkshire murderer. Seven Provisional IRA bombs exploded in the West End. The country seemed bleaker, darker, than even the blackouts of ’73. The Clash, now donned in military garb with ‘STEN GUNS IN KNIGHTSBRIDGE’ across their forearms, were at the frontline.

‘White Riot’, ‘Career Opportunities’, ‘Janie Jones’, ‘I’m So Bored With the USA’ stand amongst the band’s finest achievements, and the band would never sound so purely, unabashedly young, loud and punk.

The relationship with the label was often acrimonious, best defined the label releasing ‘Remote Control’ against the band’s wishes. The band were already hyper-conscious of accusations of selling out, and already irked by Rhodes’ increasing demand for power. Luckily, these grievances ignited them. The result was ‘Complete Control’ – the most anti-CBS CBS single. It’s a ridiculously compelling track, seething with resentment, fury, betrayal. At once a fierce polemic against corporations, management and the scene itself – it remains a defiant act of resistance, and a thrilling defence of the band’s vision and autonomy.

The Sex Pistols, meanwhile, were public enemy number one.

They performed ‘God Save the Queen’ on the Thames two days before the Jubilee, and they faced open assault in the streets, and in the press. The group was coming apart at the seams. They would barely survive ’77, a living circus.

“No Elvis, no Beatles in 1977” sang Strummer – and soon no Sex Pistols. Sid Vicious wouldn’t live to see the 80s. Punk itself would barely limp into the next decade. It was testament to the Clash’s hardiness and spirit of reinvention that they had lasted this long.

Give ‘Em Enough Rope was released in 1978, a rallying cry for a bruised and beaten scene. It was brazen and loud, a perfect piece of punk populism. It’s full of deeply funny moments of self-doubt and deprecation (‘Safe European Home’, ‘Guns on the Roof’), yet it’s a confident, striding and forceful set of songs. It seemed like the Clash were emerging victorious after the bloody mess of the last two years. They would end the decade having cemented their legacy, musically – and socially.

Rock Against Racism had been brewing since 1976, as a protest against the rise of far-right politics, which had come in from the fringes and was practically Conservative policy by ’78. In the spring, 100,000 people marched from Trafalgar Square to the heart of the East End. The Clash would play a free gig in Victoria Park, alongside Buzzcocks, Misty in Roots, X-Ray Spex. It was a brilliant manifestation of the band’s desire for active displays of racial solidarity in the punk movement. The campaign did infinitely brilliant work in wrestling the scene from its fascist connotations, even if the gig itself suffered from poor sound – the PA system was ordered based on an estimated 15,000 attending: it was five times that.

The Clash’s optimism and socialism seemed to come to fruition.

They were now ready to return to the studio as a group that had outgrown their punk roots by making their sound infinitely richer. Their long flirtation with reggae, funk, folk, calypso and rockabilly would now help create their definitive statement: London Calling. The title imitated their stature: they were now broadcasting to the world. It was bigger than anything the band – or the whole scene – had ever attempted before, its social-realist message now tackling the Cold War, and nuclear Armageddon. The album is pierced with weird howls, and thunderclaps, it carries a monumental horror and power. It’s a devastating summation of the 1970s.

Simonen’s hovering, doomed bass graces the brilliantly Elvis-baiting front cover, poised to destroy everything in its wake. Now definitely a Huge Rock ‘n’ Roll band, The Clash dug in, and opened their ears beyond West London.

They were intoxicated by the emergent hip-hop sound emanating from the Bronx, and never cautious about trying on new styles, they recorded ‘The Magnificent Seven’ in April 1980. Their genuine, youthful exuberance and sincerity has never been more apparent. Strummer sounds remarkably assured, considering the novelty of the attempt, buoyed by one of the most irresistible basslines they ever recorded (by Norman Watt-Ray from the Blockheads – Simonen was filming Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains, a film that was already looking back on the punk era).

This was entirely new territory, not just for The Clash, but for the entire music industry

.

Sugarhill Gang’s ‘Rapper’s Delight’ was just four months old – Grandmaster Flash wouldn’t release ‘The Message’ until July 1982. It was months before Debbie Harry would go on a personal mission to establish crossover hip-hop, cutting ‘Rapture’ – the first US No.1 to feature “rap” in January 1981- before introducing Funky Four Plus One to millions on Saturday Night Live a month later.

The Clash, and especially Mick Jones, were so enamoured with hip-hop, just as they always been with reggae and dub, that they pre-empted the genre’s all-conquering future. It’s a key example of The Clash celebrating their influences in such an obviously loving and earnest way, that it’s impossible to deride them as cynical or appropriative. Quite the opposite, they were the epitome of a hopeful spirit that musical influence between genres and races could benefit all.

It was the perfect opening gambit to the decade ahead, where cross pollination between genres would be rampant.

Meanwhile, back home in Parliament, James Callaghan had somehow made it through to 1979, but following the Winter of Discontent, and he finally succumbed to a vote of no confidence, which squeaked through the House by one vote in March. The Conservatives won the subsequent May ’79 election with a majority of 43, and Thatcher stood on the steps on Downing Street with a steely resolve, promising to bring harmony where there had been discord, and clashes.

She wanted to restore the glory and order of a Great Britain. She reanimated a ghostly vision of a lost British past, built on the Empire, Union Jacks, long shadows on cricket grounds and respect for authority. A hierarchical Britain, where people did as they were told. To many, it was an elitist, retrograde fiction. To others, especially those who had lived through the war, it was a powerful vision which promised to bring stability in a country plagued by industrial dispute and decaying cities, where the dustbins overflowed and revolting punks ran around, untamed. In retrospect, her victory seems like the symbolic full stop on the punk era, as definitive and final as Altamont was for the hippy era a decade before.

But the Clash had outlived the genre, and would go onto three more sprawling, ambitious albums. They were now joined by an explosion of new sounds.

The decade ahead would be in equal parts traumatic and exciting, and the political and artistic endeavours of the 1980s would be nothing quite like anything before. Part of punk’s power wasn’t particularly its musical invention. It lacked the future-shock sound of ‘I Feel Love’, or ‘Planet Rock’. It was rooted, and would mostly remain, socially and sonically in the late 70s, and its shock was to force its country to stare itself in the face. In the face of a Thatcherite government, it seemed other scenes were waking up too.

Out of the ashes of a burnt out punk scene, new pop and post punk bought outsiders and experiments to the fore. By the turn of the decade, Joy Division had released ‘Unknown Pleasures’ and Blondie were performing ‘Denis’ on Top of the Pops. A new dawn.

It’s clear how much of the early eighties new radical pop was born from either a reaction to or veneration of punk’s ideals. Post punk shared punk’s Year Zero mission statement (“rip it up and start again…”) and The Clash’s politics; indie shared its anti-establishment agenda, yet fetishised 60s pop which punk had loathed. Metal assumed its noise and adopted showy acts of rebellion.

Bands like The Jam sprung from the punk scene, yet were clearly influenced from the 60s mod scene, upholding a curious sense of English revivalism which has carried on through Madness and Oasis. Acid house would welcome everyone under its tent, a blissed out communion of kids, and it was loathed and feared by the press in a frenzy not seen since 1976. Hip-Hop exploded at the turn of the decade – a genre that has honestly and explicitly pursued a working class narrative, despite its enormous commercial success.

The poptimists like Adam Ant saw Top of the Pops as their stage – a place to aspire to rather than distrust. And Britain was ready to dance again.

The Clash had yanked punk out from its nasty doldrums and had spawned disciples and deniers that would shape the next decade and beyond.

Their sprawling, contradictory career was many things, but it was never boring. Their output was astonishing, in its quality, its restless spirit and ambition. And they were fun! Listen to all seventeen singles without grinning madly, howling, or punching your knee… This is a Public Service Announcement… with guitars!

They had sprung from the same crises as the Pistols, but where Rotten and Vicious seemed to want to exacerbate and spark emergency, The Clash sought communal, human ways to improve their world: rebellion over nihilism. They were preoccupied with upheaving the cultural standards of their time; they were revolutionaries and outlaws beyond sloganeering. Their sound outgrew punk’s norms rapidly; more daring in its diversity, more intelligent and empathetic in its anger. They were never shy about forefronting their politics, unbowed and unafraid, the last gang against the ice-age, Tommy-guns in hand.

It’s this mythology that gets handed down, their story now nearly 40 years older. Reflecting on it reveals its contradictions, its missteps and its thrills.

But The Clash have endured, triumphant – the only band that ever mattered.

– James Mackey

The Clash – ‘Combat Rock/The People’s Hall’ Special Edition Album

Originally released in May 1982, ‘Combat Rock’ is the biggest and highest charting final album from The Clash and features two of the band’s most popular songs ‘Should I Stay Or Should I Go’ and ‘Rock The Casbah’.

Read more

The Clash Celebrate 40th Anniversary of ‘Sandinista!’

To mark the 40th anniversary of their album ‘Sandinista!’ The Clash have released a video for “The Magnificent Seven” shot and edited by filmmaker Don Letts.

Read more

VIDEO OF THE WEEK: THE CLASH – ‘LONDON CALLING’

This memorable and iconic video for the title track from The Clash’s third album was only the second promo to be shot by director Don Letts.

Read more

THIS WEEK IN ROCK

A week of lyrical landmarks, timeless trivia and record-breaking record releases, it’s This Week In Rock…

Read more

THIS WEEK IN ROCK

Many happy returns, TV debuts, landmark record deals and more. It’s This Week In Rock.

Read more

This Week In Rock

History-making meetings, career-defining releases, epoch-engendering live shows and more – it’s This Week In Rock…

Read more

THIS WEEK IN ROCK

Ever wondered what history’s biggest rock stars were up to over the festive period? Wonder no longer, it’s This Week In Rock…

Read more

THIS WEEK IN ROCK

Legendary shows, groundbreaking album anniversaries, eye watering memorabilia auctions and more – it’s this week in rock.

Read more

Artist of the Month: The Clash

As a very special edition of 1979’s ‘London Calling’ hits the shelves, and the accompanying exhibition is due to open at the Museum of London, punk legends The Clash are our Artist of the Month for November.

Read more